Difference between revisions of "IPS implementationguide 1"

(→Conformance clause) |

(→Conformance clause) |

||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

There are no additional requirements to be applied for this guide for what concern the Recipient and the Originator Responsibilities. | There are no additional requirements to be applied for this guide for what concern the Recipient and the Originator Responsibilities. | ||

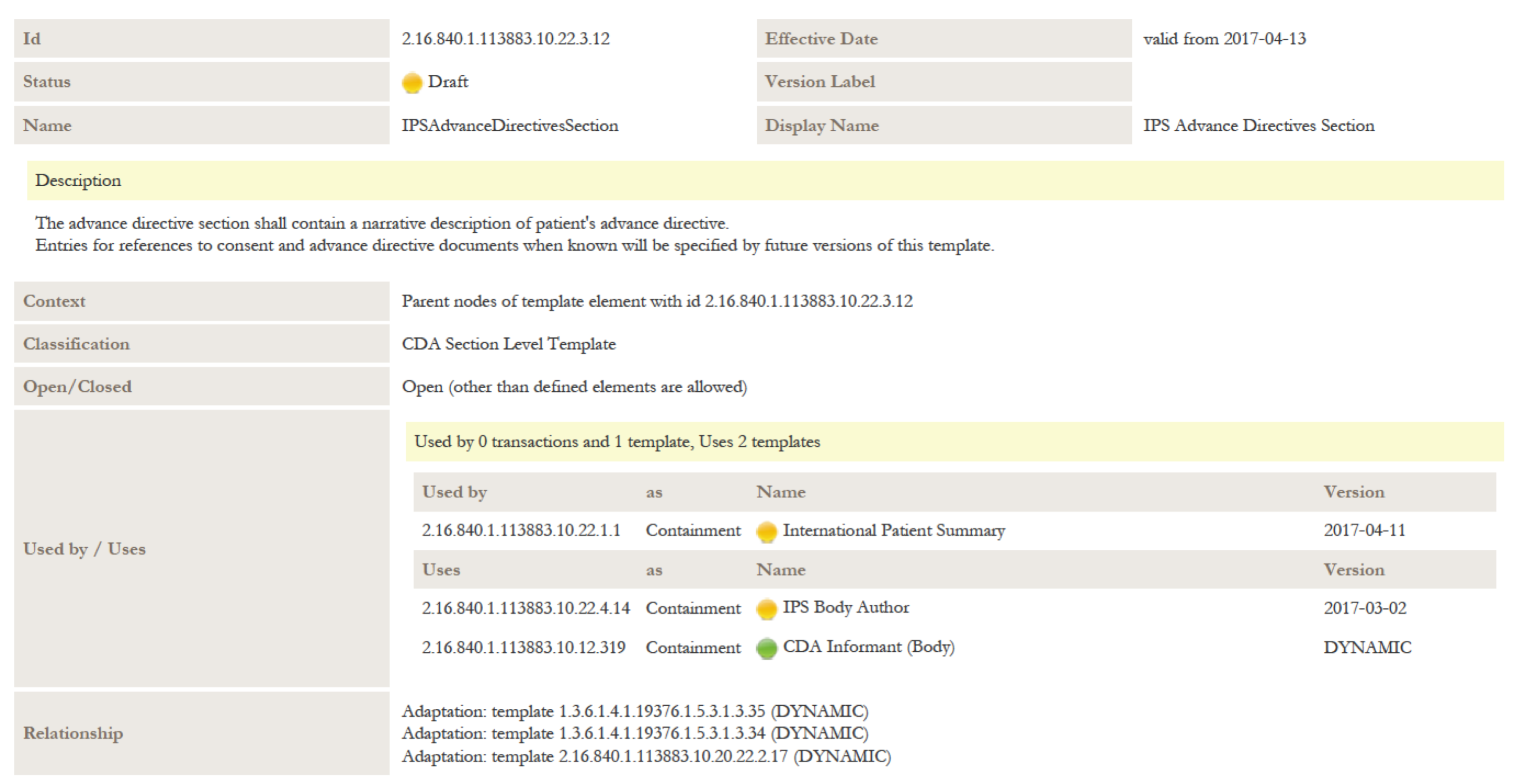

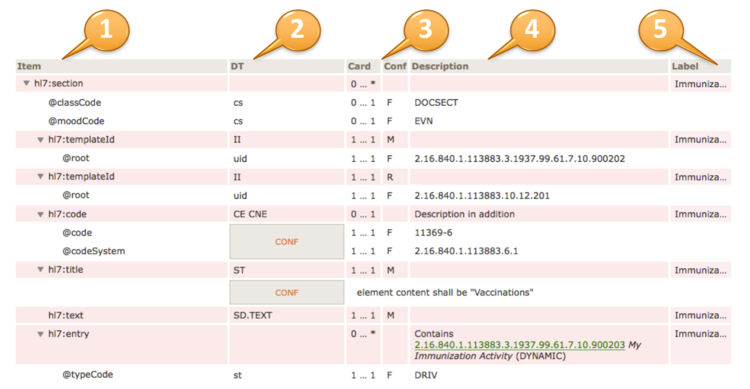

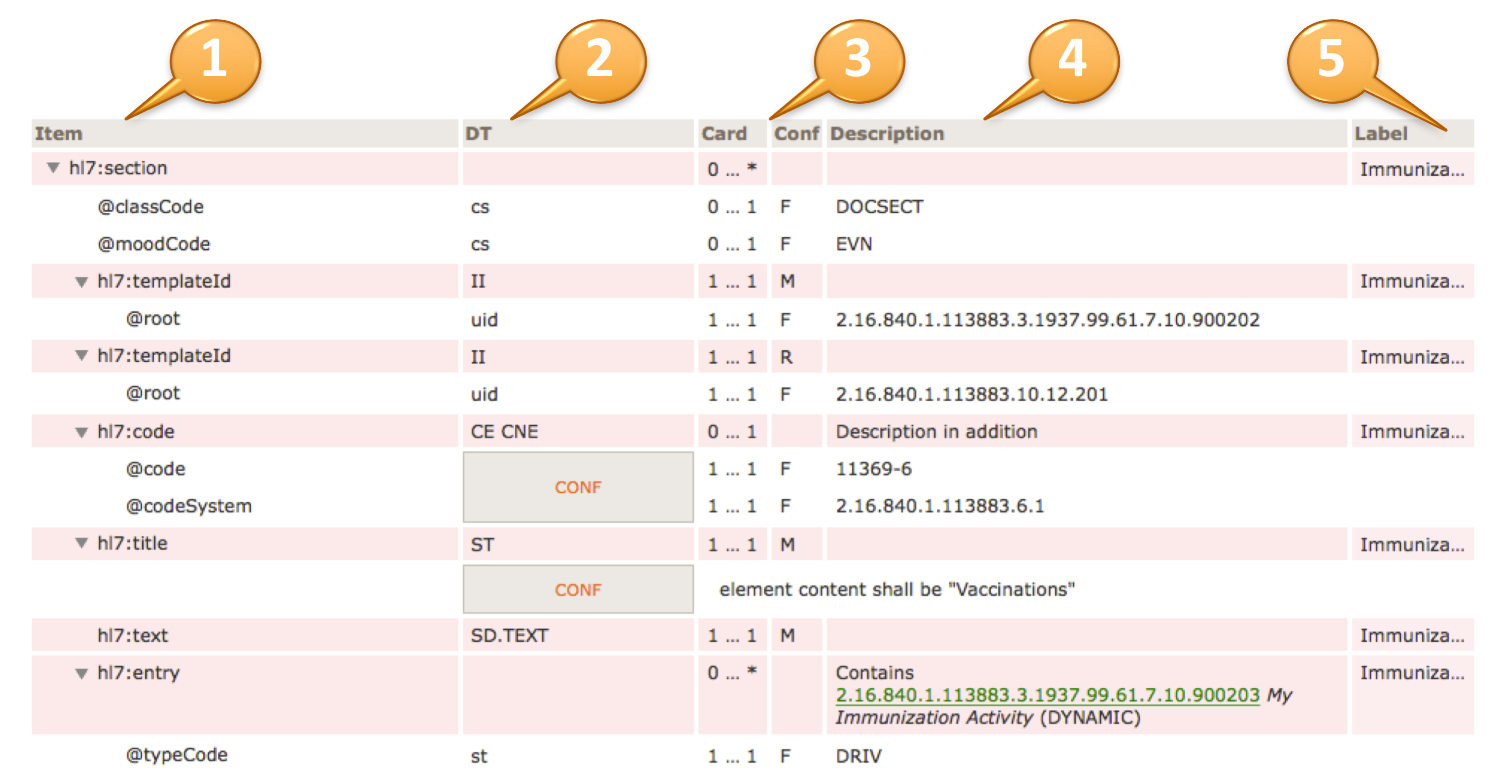

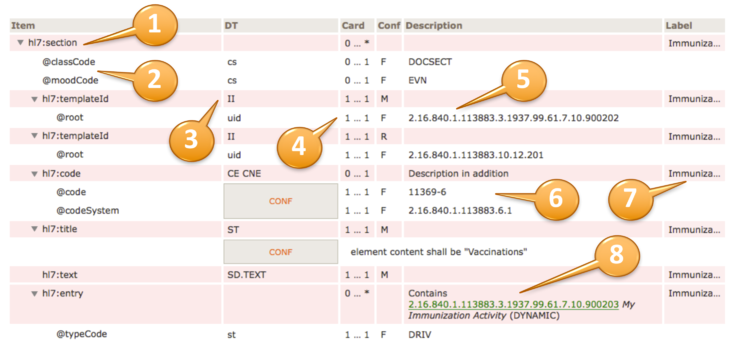

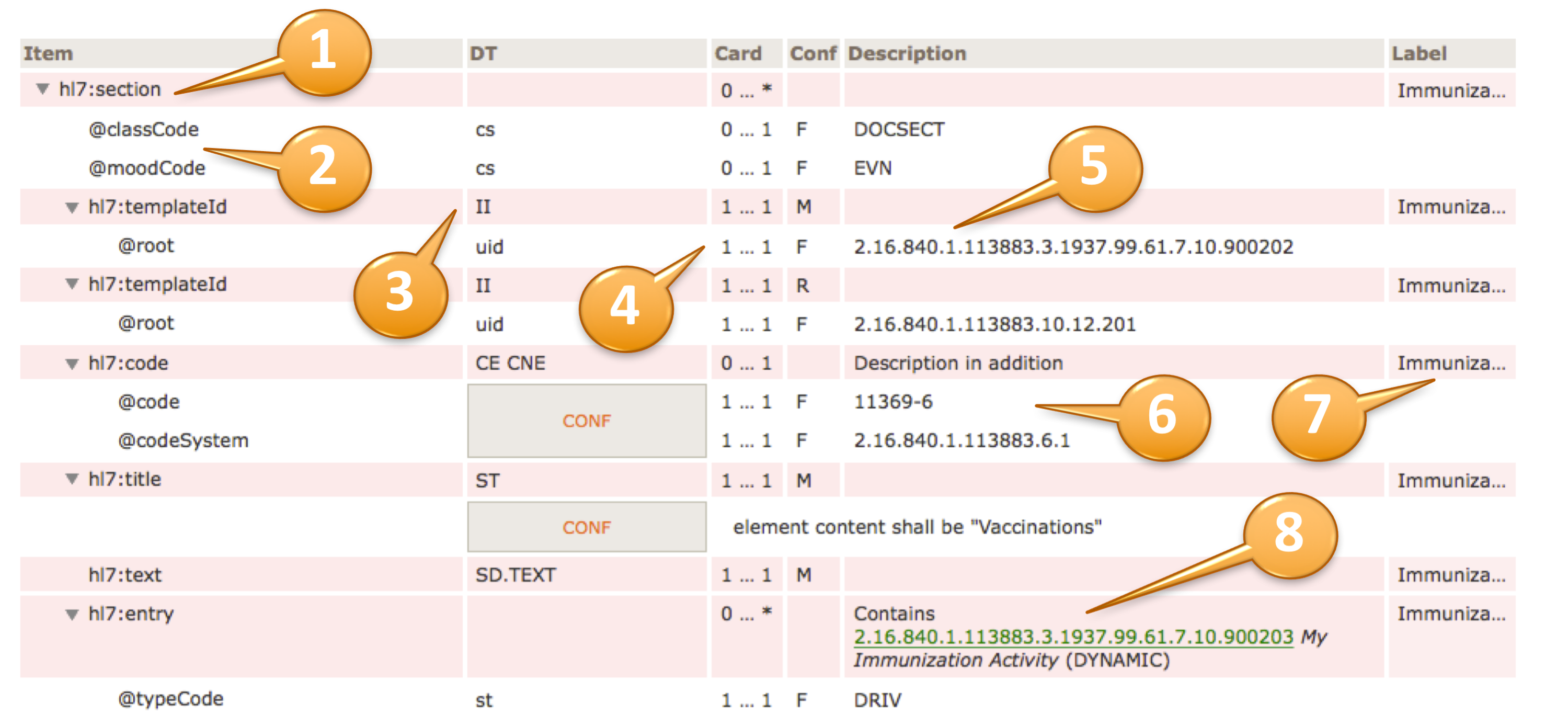

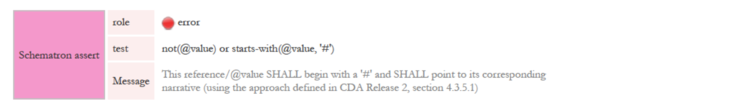

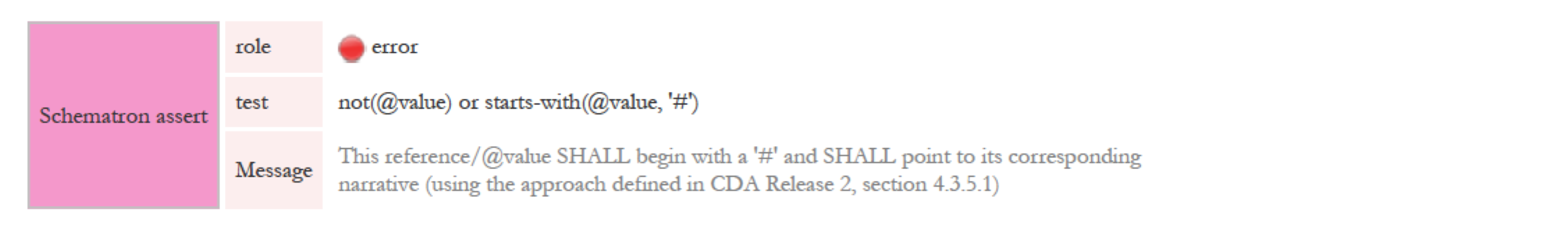

| − | The formal representation used in this implementation guide for expressing the conformance statement is described in section "[[ | + | The formal representation used in this implementation guide for expressing the conformance statement is described in section "[[Reading_Guide_for_Publication_Artifacts]]" of this guide and makes use of a tabular representation that may include also computable or textual constraints. The template rules are formalized using the computable format defined by the HL7 Templates Standard: Specification and Use of Reusable Information Constraint Templates, Release 1<ref name="teits">HL7 Templates Standard: Specification and Use of Reusable Information Constraint Templates, Release 1 http://www.hl7.org/implement/standards/product_brief.cfm?product_id=377</ref> in order to facilitate also the automatic generation of consistent testing and validation capabilities. |

This standard (i.e. the HL7 Templates Standard: Specification and Use of Reusable Information Constraint Templates, Release 1 ) defines also how derived templates may relate to the templates defined in this guide for example: | This standard (i.e. the HL7 Templates Standard: Specification and Use of Reusable Information Constraint Templates, Release 1 ) defines also how derived templates may relate to the templates defined in this guide for example: | ||

Revision as of 17:03, 30 July 2017

This document contains: Implementation Guide International Patient Summary (0.95). The text materials belong to category cdaips.

International Patient Summary, Release 1

© 2016-2017 Health Level Seven International ® ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

The reproduction of this material in any form is strictly forbidden without the written permission of the publisher. HL7 and Health Level Seven are registered trademarks of Health Level Seven International. Reg. U.S. Pat & TM Off.

HL7 licenses its standards and select IP free of charge. If you did not acquire a free license from HL7 for this document, you are not authorized to access or make any use of it. To obtain a free license, please visit http://www.HL7.org/implement/standards/index.cfm.

If you are the individual that obtained the license for this HL7 Standard, specification or other freely licensed work (in each and every instance "Specified Material"), the following describes the permitted uses of the Material.

A. HL7 INDIVIDUAL, STUDENT AND HEALTH PROFESSIONAL MEMBERS, who register and agree to the terms of HL7’s license, are authorized, without additional charge, to read, and to use Specified Material to develop and sell products and services that implement, but do not directly incorporate, the Specified Material in whole or in part without paying license fees to HL7.

INDIVIDUAL, STUDENT AND HEALTH PROFESSIONAL MEMBERS wishing to incorporate additional items of Special Material in whole or part, into products and services, or to enjoy additional authorizations granted to HL7 ORGANIZATIONAL MEMBERS as noted below, must become ORGANIZATIONAL MEMBERS of HL7.

B. HL7 ORGANIZATION MEMBERS, who register and agree to the terms of HL7's License, are authorized, without additional charge, on a perpetual (except as provided for in the full license terms governing the Material), non-exclusive and worldwide basis, the right to (a) download, copy (for internal purposes only) and share this Material with your employees and consultants for study purposes, and (b) utilize the Material for the purpose of developing, making, having made, using, marketing, importing, offering to sell or license, and selling or licensing, and to otherwise distribute, Compliant Products, in all cases subject to the conditions set forth in this Agreement and any relevant patent and other intellectual property rights of third parties (which may include members of HL7). No other license, sublicense, or other rights of any kind are granted under this Agreement.

C. NON-MEMBERS, who register and agree to the terms of HL7’s IP policy for Specified Material, are authorized, without additional charge, to read and use the Specified Material for evaluating whether to implement, or in implementing, the Specified Material, and to use Specified Material to develop and sell products and services that implement, but do not directly incorporate, the Specified Material in whole or in part. NON-MEMBERS wishing to incorporate additional items of Specified Material in whole or part, into products and services, or to enjoy the additional authorizations granted to HL7 ORGANIZATIONAL MEMBERS, as noted above, must become ORGANIZATIONAL MEMBERS of HL7. Please see http://www.HL7.org/legal/ippolicy.cfm for the full license terms governing the Material.

Ownership. Licensee agrees and acknowledges that HL7 owns all right, title, and interest, in and to the Materials. Licensee shall take no action contrary to, or inconsistent with, the foregoing.

Licensee agrees and acknowledges that HL7 may not own all right, title, and interest, in and to the Materials and that the Materials may contain and/or reference intellectual property owned by third parties (“Third Party IP”). Acceptance of these License Terms does not grant Licensee any rights with respect to Third Party IP. Licensee alone is responsible for identifying and obtaining any necessary licenses or authorizations to utilize Third Party IP in connection with the Materials or otherwise. Any actions, claims or suits brought by a third party resulting from a breach of any Third Party IP right by the Licensee remains the Licensee’s liability.

Following is a non-exhaustive list of third-party terminologies that may require a separate license:

| Terminology | Owner/Contact |

|---|---|

| Current Procedures Terminology (CPT) code set | American Medical Association https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/cpt-licensing |

| SNOMED CT© | SNOMED International http://www.snomed.org/snomed-ct/get-snomed-ct or info@ihtsdo.org |

| Logical Observation Identifiers Names & Codes (LOINC©) | Regenstrief Institute, Inc. |

| International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes | World Health Organization (WHO) |

| NUCC Health Care Provider Taxonomy code set | American Medical Association. Please see www.nucc.org. AMA licensing contact: 312-464-5022 (AMA IP services) |

| Primary Editor | Giorgio Cangioli, PhD Consultant, HL7 Italy giorgio.cangioli@gmail.com |

| Primary Editor | Rob Hausam Hausam Consulting LLC rob@hausamconsulting.com |

| Primary Editor | Dr Kai U. Heitmann Heitmann Consulting and Services, HL7 Germany, ART-DECOR Open Tools GmbH info@kheitmann.de |

| Primary Editor | François Macary Phast francois.macary@phast.fr |

| Contributor | Dr Philip Scott HL7 UK philip.scott@uwtsd.ac.uk |

| Contributor | Dr Christof Geßner Gematik christof.gessner@gematik.de |

| Contributor | Dr Stefan Sabutsch ELGA, HL7 Austria stefan.sabutsch@elga.gv.at |

| Contributor | Gary Dickinson CentriHealth gary.dickinson@ehr-standards.com |

| Contributor | Catherine Chronaki HL7 International Foundation chronaki@gmail.com |

| Contributor | Dr Stephen Chu HL7 Australia chuscmi88@gmail.com |

| Contributor | Didi Davis The Sequoia Project ddavis@sequoiaproject.org |

| Other Contributors | Alexander Berler (a.berler@gnomon.com.gr) ; Carina Seerainer (carina.seerainer@elga.gv.at); John Roberts (John.A.Roberts@tn.gov); Julie James (julie_james@bluewaveinformatics.co.uk); Mark Shafarman (mark.shafarman@earthlink.net); Fernando Portilla (fportila@gmail.com); Ed Hammond (william.hammond@duke.edu); Steve Kay (s.kay@histandards.net) |

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Technical Background

- 3 Functional requirements and high-level use cases

- 4 Design conventions and principles

- 4.1 How to use terminologies (preferred binding)

- 4.2 Representing "known absent" and "not known"

- 4.3 Uncoded information

- 4.4 Unmapped Coded Concepts

- 4.5 Mapped coded concepts

- 4.6 Translation of designations

- 4.7 Narrative Translations

- 4.8 Determining the Status of Clinical Statement

- 4.9 The use of medication statements in the summary

- 4.10 Medicinal Product Identification

- 4.11 Provenance

- 4.12 Representation of Names

- 5 Conformance clause

- 6 Appendix (Informative)

- 7 List of all artifacts used in this guide

- 8 How to read the table view for templates

- 9 References

Introduction

An International Patient Summary (IPS) document is an electronic health record extract containing essential healthcare information intended for use in the unscheduled, cross-border care scenario, comprising at least the required elements of the IPS dataset. The IPS dataset is a minimal and non-exhaustive patient summary dataset, specialty-agnostic, condition-independent, but readily usable by clinicians for the cross-border unscheduled care of a patient.

Purpose

The goal of this Implementation Guide is to identify the required clinical data, vocabulary and value sets for an international patient summary. The international patient summary is specified as a templated document using HL7 CDA R2. The primary use case is to provide support for cross-border or cross-juridictional emergency and unplanned care.

This specification aims to support:

- Cross-jurisdictional patient summaries (through adaptation/extension for multi-language and realm scenarios, including translation).

- Emergency and unplanned care in any country, regardless of language.

- Value sets based on international vocabularies that are usable and understandable in any country.

- Data and metadata for document-level provenance.

Project Background

This Implementation Guide has drawn upon the results of multiple previous projects on patient summaries (including but not limited to epSOS [1], ONC S&I, Trillium Bridge[2], Sequoia eHealth Exchange [3]), rules and recommendations for vocabularies and value sets (in multilingual settings) and templates for the implementation of international patient summary documents.

The idea of the International Patient Summary has been one of the main results of the 2010 EU/US Memorandum of Understanding through its two operational arms: the European project Trillium Bridge and the Interoperability of EHR work group formed under the ONC Standards and Interoperability Framework (ONC S&I) EU/US eHealth Cooperation Initiative[4]. These initiatives identified the need for common templates and vocabularies for the patient summary.

The Joint Initiative Council (JIC) on SDO Global Health Informatics Standardization has initiated the standard sets project with patient summary as its pilot [5]; and the IPS became one of the main subjects of the new EU / US roadmap , having as a declared goal “to enable a standardized international patient summary (IPS) to be in use by 2020”[6].

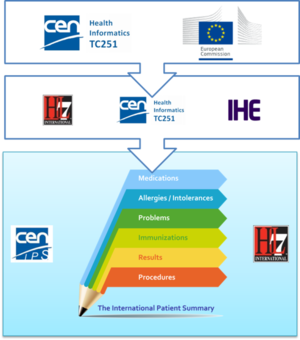

The first standardization activity concerning the IPS was initially promoted in April 2014 by ONC within HL7 International. The project was called “INTernational PAtient Summary (INTERPAS)”. In May 2016, the European Commission granted an Agreement with CEN/ TC 251, recognizing the need to effectively support the leadership and active participation in IPS standardization activities. Thanks to the new boost from the European Commission (EC) and ONC a revision of the HL7 project was started in May 2016, as well as the standardization activities in CEN/TC 251 for the European standards on Patient Summaries. Since the beginning of this new phase, the initiatives were envisaged as a single common IPS project supported by different organizations; where the CEN/TC 251 and the HL7 teams worked together, taking in account the inputs of the JIC Standard Sets initiative on Patient Summary, with the common intent of developing coherent set of standards to support the International Patient Summary concept.

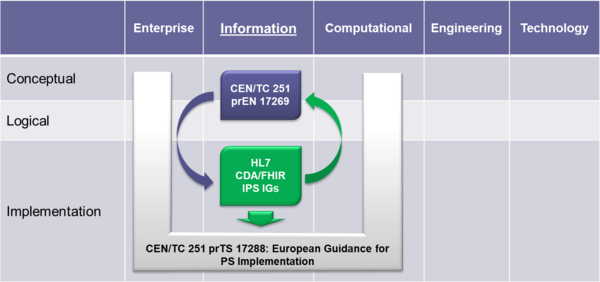

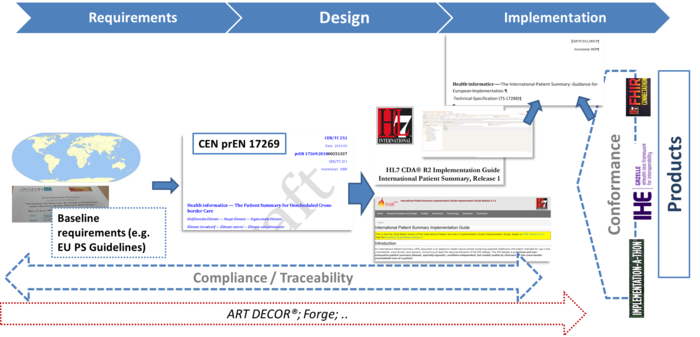

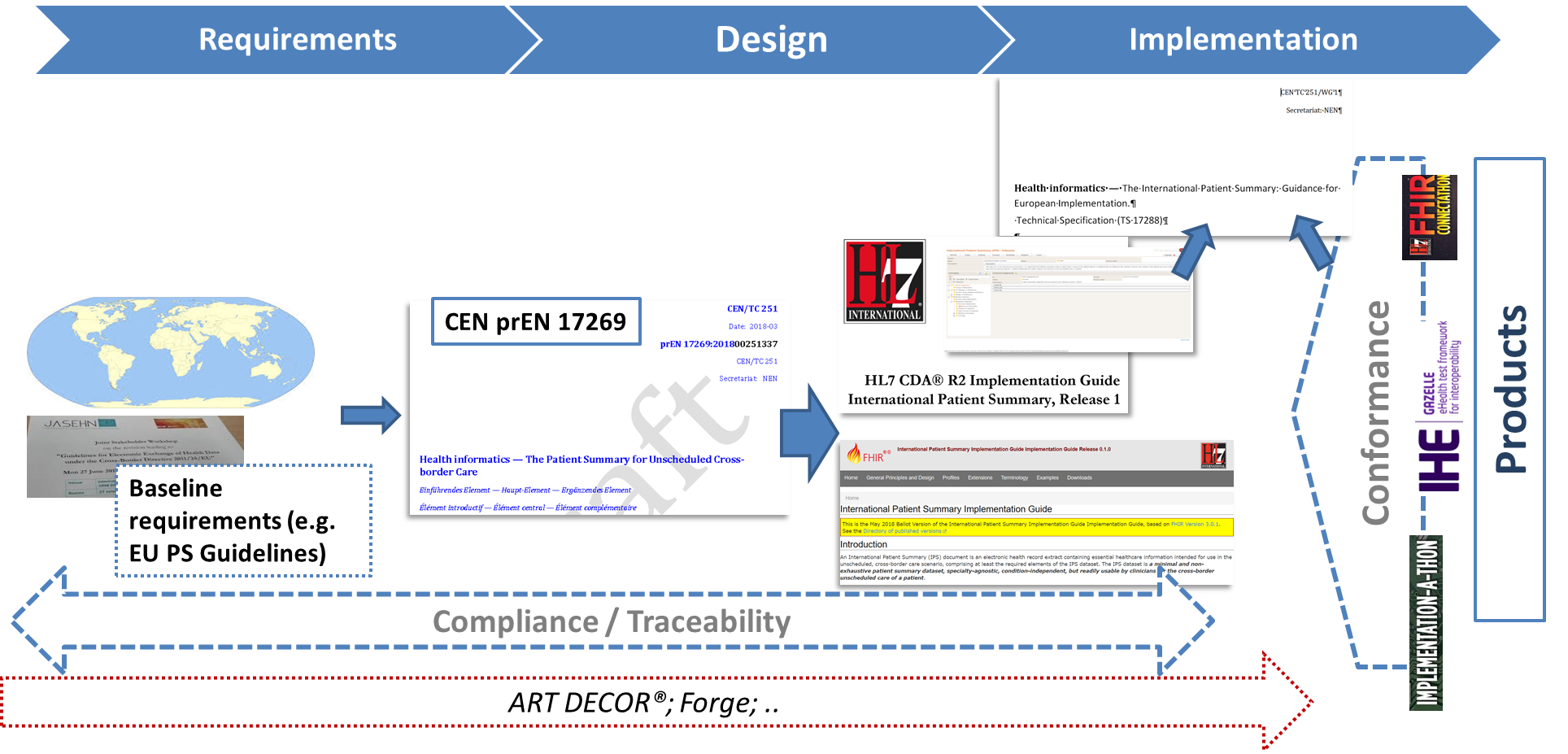

To expedite progress it was also agreed to set up an informal collaboration, promoting a continuous alignment process between the two SDO-specific projects, thanks also to a cross-participation in the project teams. Overlaps have thus been minimized: the CEN/TC 251 activities have been focused on the IPS dataset, formalized by the CEN/TC 251 Draft European standard (prEN) 17269:2018: The Patient Summary for Unscheduled, Cross-border Care" (the CEN/TC 251 prEN 17269:2018 PS in [Figure 1]); the HL7 ones initially on its implementation based on HL7 CDA R2 - this guide - and next on FHIR (the HL7 IPS IGs in [Figure 1]). The figure shows how the products of these standardization activities are placed in the HL7 SAIF Interoperability Matrix.

[Figure 1] IPS Standards in the HL7 SAIF Interoperability Matrix

A formal agreement between HL7 International and CEN/TC 251 has been finally signed in April 2017 in which these organizations established “in order to further the care for citizens across the globe <…> to collaborate on a single, common International Patient Summary (IPS) specification”; and that “the IPS specification shall focus on a minimal and non-exhaustive Patient Summary dataset, which is specialty-agnostic and condition-independent, but still clinically relevant.”.

Scope

As expressed in the introduction, the International Patient Summary is

- a minimal and non-exhaustive patient summary,

- specialty-agnostic,

- condition-independent,

- but readily usable by clinicians for cross-border unscheduled care of a patient.

In this context, minimal and non-exhaustive means that an IPS is not intended to reproduce (the entire) content of an Electronic Health Record (EHR).

Specialty-agnostic means that an IPS is not filtered for a specialty. As an example, allergies are not filtered to the specialty of internal medicine, thus may also include food allergies, if considered to be relevant for, e.g. unplanned care.

Condition-independent means that an IPS is not specific to particular conditions, and focuses on the patient current condition(s).

Furthermore the scope of the IPS is global. Although this is a major challenge, this implementation guide takes various experiences and newer developments into account to address global feasibility as far as possible.

General Principles for this Specification

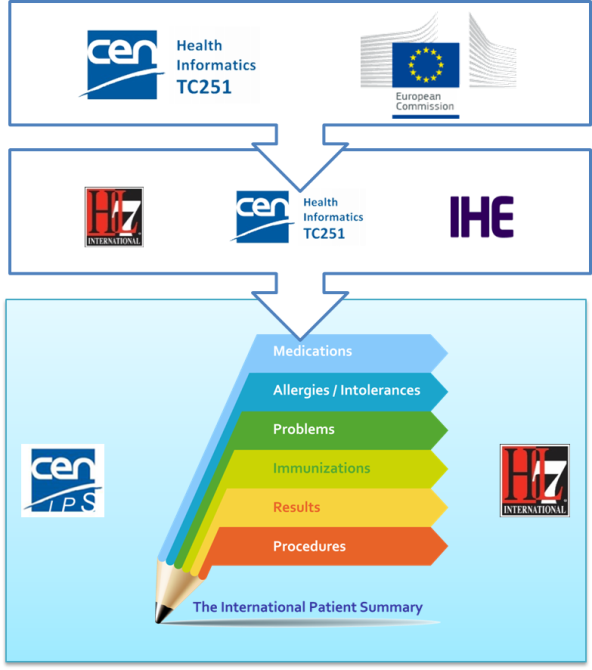

With the formal agreement signed on April 2017, HL7 International and CEN/TC 251 expressed their intent to collaborate under the following principles for the IPS:

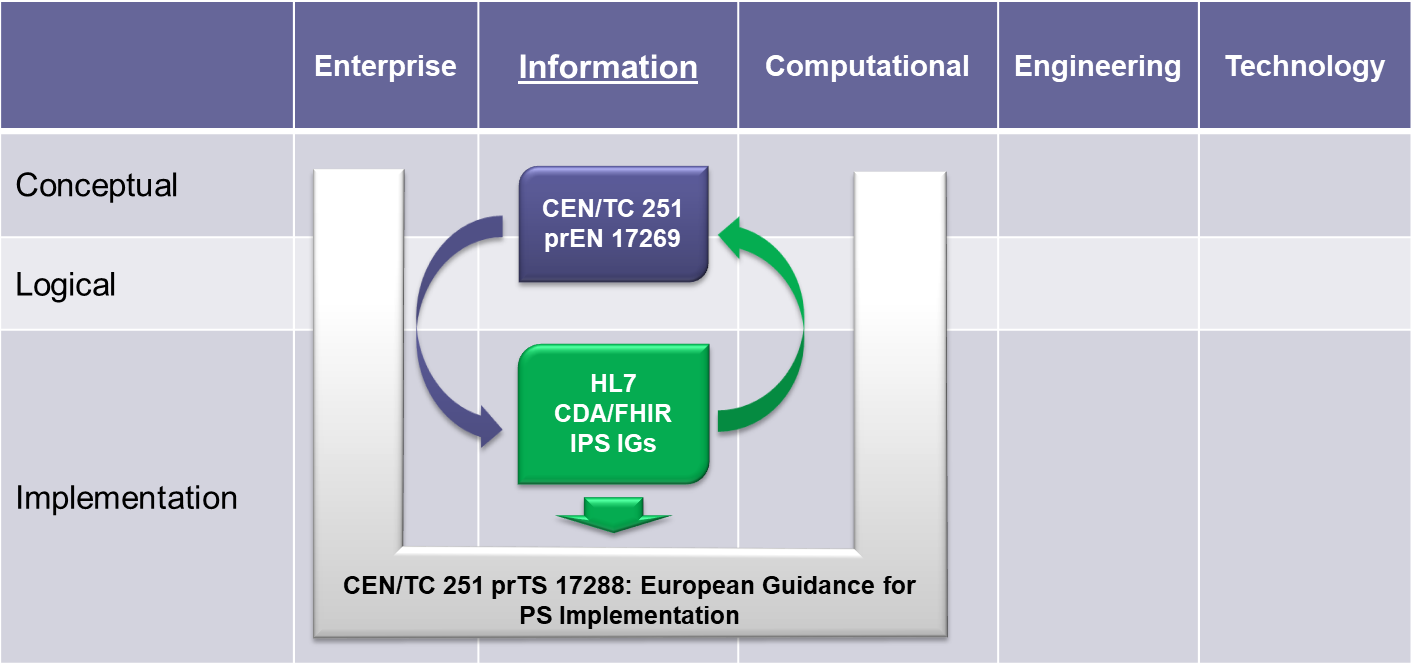

[Figure 2] The IPS Principles

- The standards specification for the IPS will be implementable

- Promote (the evolution and convergence of) existing standards

- Rely on solutions that are already implemented or ready for implementation

- Consider new or additional solutions as they become available

- The standards specification for the IPS will be applicable for global use

- Strive for global accessibility of standards for use at no cost

- Strive for a core set of globally accessible and usable terminologies and value sets

- Include free text in addition to the structured codes as needed

- Do not include local solutions in the core specification that are not available in other jurisdictions

- The standards specification will be extensible and open to future use cases and solutions

- The IPS provides common content that can be extended and specialized for other use cases, or localized for specific jurisdictional needs

- The IPS is open to emerging solutions for unresolved issues or improvements

- The standards specification and their implementation must be sustainable through:

- A robust maintenance and update process for the IPS

- A process to ensure clinical validity of the IPS, meeting:

- clinical requirements (including workflow)

- clinical documentation requirements

- information quality requirements

Moreover HL7 International and CEN/TC 251 will manage the expectations of the IPS standards specification among stakeholders, by

- stipulating the role of the IPS as a foundation for others to extend

- justifying the inclusion of items in the IPS within the limited context of cross-border or cross-jurisdiction unscheduled care.

The more relevant consequences of these principles in the template design are:

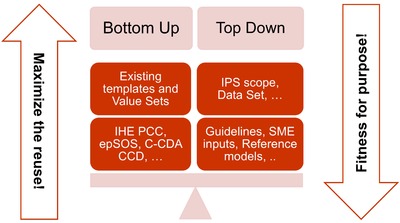

- The adoption of a meet in the middle approach in the templates design to balance the need of maximizing the reuse of existing implemented templates (epSOS, C-CDA CCD; IHE PCC…) and facilitate implementation with the need of optimizing the fitness for purpose within the IPS scope. This approach aims to avoid a pure technical exercise of templates harmonization or an academic exercise that does not take in account what is already implemented.

[Figure 3] The IPS meet-in-the-middle approach

- Cooperate with the HL7 Terminology Authority and the organizations that own the used code systems (e.g. SNOMED International) to make the IPS value sets available for global use at no cost for implementation of the IPS.

- When global identifiers are not (or not yet) available, as in the case of the medicinal products, enhance the model proposed for that element with relevant identifying and descriptive attributes that could help with the global identification of that element.

- Select a set of global reference terminologies, with provision for the inclusion of locally used terminologies.

- Avoid solutions (e.g. identifiers, terminologies, standards) that are not yet available for actual global use (even those that are otherwise promising for resolution of well-known issues, such as medicinal product identification). However, the IPS has been already designed, where possible, to be ready to adopt these solutions when they are made available for real use (e.g. the IDMP identifiers) and to already support parts of those solutions that can be used today.

- Within the scope of the IPS and of the “implementable” principle, attempt to be sufficiently generic in the design of the templates so that the IPS templates are extensible for supporting new scenarios, specific specialties or conditions through template specialization or adaptation mechanisms.

Structuring Choices

The International Patient Summary is specified as a templated document using HL7 CDA R2. The expressiveness of SNOMED CT and other primary terminologies enables this specification to represent the two general categories “condition/activity unknown” and “condition/activity known absent” in a style which is more independent of the underlying syntax (CDA R2 or FHIR), as explained in detail in section 4.2.

To be universally exchangeable and understood, a patient summary must rely as much as possible on structured data and multilingual international reference terminologies that are licensed at no cost for global use in the International Patient Summary. In the case of SNOMED CT, it is envisioned that SNOMED International could embrace the idea of a globally accessible open and free specification for the International Patient Summary that references a core set of globally accessible and usable value sets licensed at no-cost with the aim to serve the public good. In this spirit, this version of the International Patient Summary defines SNOMED CT as a primary terminology (the meaning of "primary terminology" is explained in section 4.1) and it is used in many of the value sets. To allow, however, a global and free implementation of the IPS this guide does not impose the usage of these SNOMED CT-based value sets. This choice may be revised in future versions. Other primary terminologies used in this specification are LOINC for observations (e.g., laboratory tests) and document sections, UCUM for units of measure, and EDQM Standard Terms for dose forms and routes. Looking at the availability of other globally usable reference terminologies and toward alignment with a future FHIR version of the IPS, in some selected cases FHIR-defined terminologies are recommended.

This specification adopts ART-DECOR®[7] as the specification platform for this Implementation Guide and uses the HL7 template exchange format[8]. This tool and format are increasingly used by several regions, including European countries, and have been adopted by the EU eHealth Digital Service Infrastructure (eHDSI) project for the operational deployment of the EU cross-borders patient summary and ePrescription services. Users of the specification can visit the IPS project page in ART-DECOR® to browse the specifications and review examples. Users may also use the tool to validate their IPS instances.

Ballot Status of the Document

This Implementation Guide is STU with the intention to go normative.

Audience

The audience for this Implementation Guide includes:

Public

- Citizens who want to carry or access their healthcare data for emergency or unplanned care purposes.

Regulatory

- Policy makers such as healthcare payers or government agencies.

- Healthcare information governance authorities and regulatory bodies.

Clinical

- Healthcare providers that offer unscheduled and emergency care.

- Healthcare providers that populate regional and national patient summaries.

Technical

- Vendors of EHR systems for unplanned care management, personal health records and mobile health data applications.

- System integrators.

- Organizations that manage regional and national patient summaries.

Relationships with other projects and guidelines

This guide is one of the products of the International Patient Summary project (see the Project Background section for details). This project relates to other projects and products as:

- The European Commission CEN/TC 251 Grant Agreement “The International Patient Summary Standards Project” (SA/CEN/GROW/EFTA/000/2015-16).

This project has as one of its goal “to participate in the creation of an International Patient Summary specification, at a global level, and turn this into a European standard, in line with the Guidelines on Minimum/Nonexhaustive Patient Summary Dataset for Electronic Exchange as adopted by the European eHealth Network"

Under this project two other standard work items have been promoted under CEN/TC 251:- The CEN/TC 251 “prEN 17269: The Patient Summary for Unscheduled, Cross-border Care”.

Its goal is to “formalise the dataset required to share information about the medical background and history of a patient …. It uses the European guidelines (version 2, November 2016) as an official source for the requirements….”

Even if it is a European standard it is designed to be applicable in a wider global context. - The CEN/TC 251 “prTS 17288: The International Patient Summary: Guidance for European Implementation Technical Specification.

Its goal is to “provide implementation guidance to support the use of the International Patient Summary dataset in a European context”

This document is focused on the European cross-country services.

- The CEN/TC 251 “prEN 17269: The Patient Summary for Unscheduled, Cross-border Care”.

- The European eHealth Network Guideline on the electronic exchange of health data under Cross-Border Directive 2011/24/EU. Release 2. [9] This Guideline, together with the general guidelines for the electronic exchange of health data under Cross-Border Directive 2011/24/EU, documents the clauses agreed among the European Countries to support the exchange of Patient Summary data for unscheduled care.

The relationships among these standards are shown in Figure 14 included in the section Conformance clause.

Listed below are other related initiatives:

- The HL7 Consolidated CDA (C-CDA) [10] implementation guide was developed and produced through the joint efforts of HL7, two Sub-Work Groups of the Office of the National Coordinator (ONC) Standards and Interoperability (S&I) Framework — Longitudinal Care Plan (LCP) and Long-Term Post-Acute Care (LTPAC) Transition) — and through the SMART C-CDA Collaborative hosted by ONC and Harvard Medical School. It provides a library of CDA templates for implementing a set of CDA documents.

This is one of the primary sources for this Implementation Guide. - The IHE Patient Care Coordination (PCC) Cross-Enterprise Sharing of Medical Summaries (XDS-MS) [11] – “defines a mechanisms to automate the sharing process between care providers of Medical Summaries, a class of clinical documents that contain the most relevant portions of information about the patient intended for a specific provider or a broad range of potential providers in different settings.” .

This is one of the primary sources for this Implementation Guide. - eHealth Digital Service Infrastructure (eHDSI) Patient Summary Service [12].This European initiative operationalizes the work done by the epSOS and EXPAND projects for the implementation of European Cross-border services for the exchange of patient summaries and ePrescriptions. This is one of the primary sources for this Implementation Guide.

- The Joint Initiative on SDO Global Health Informatics Standardization (JIC) Patient Summary Standards Set is a set of health informatics standards and related artifacts that can be used to support the implementation of a Patient Summary [13]. The definition of the Patient Summary given by this initiative is a little broader than that adopted by the HL7 and CEN/TC 251 projects, being ““the minimum set of information needed to assure healthcare coordination and the continuity of care” .

- The Data Provenance is an ONC S&I initiative addressing the “source data” challenge so that trust in the authenticity of the data can help inform decision making. The HL7 CDA® Release 2 Implementation Guide: Data Provenance, Release 1[14] is one of the products resulting from the joint efforts of Health Level Seven (HL7) and the Office of the National Coordinator (ONC) Standards and Interoperability Standards and Interoperability Framework-Data Provenance Initiative.

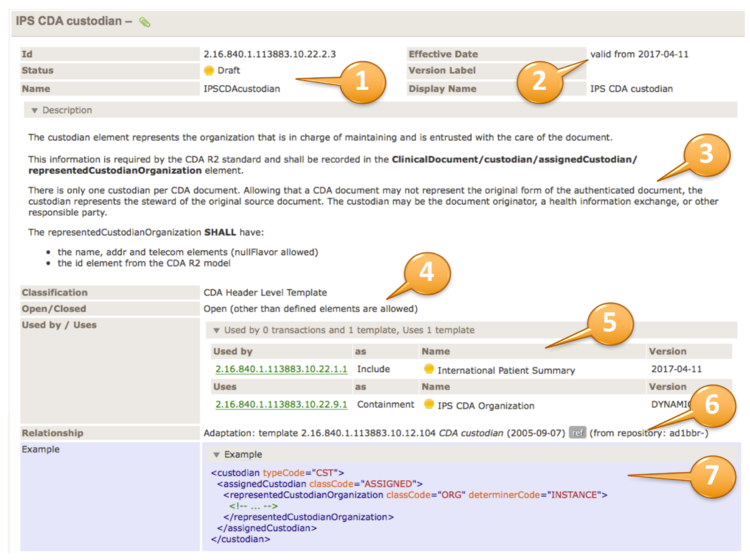

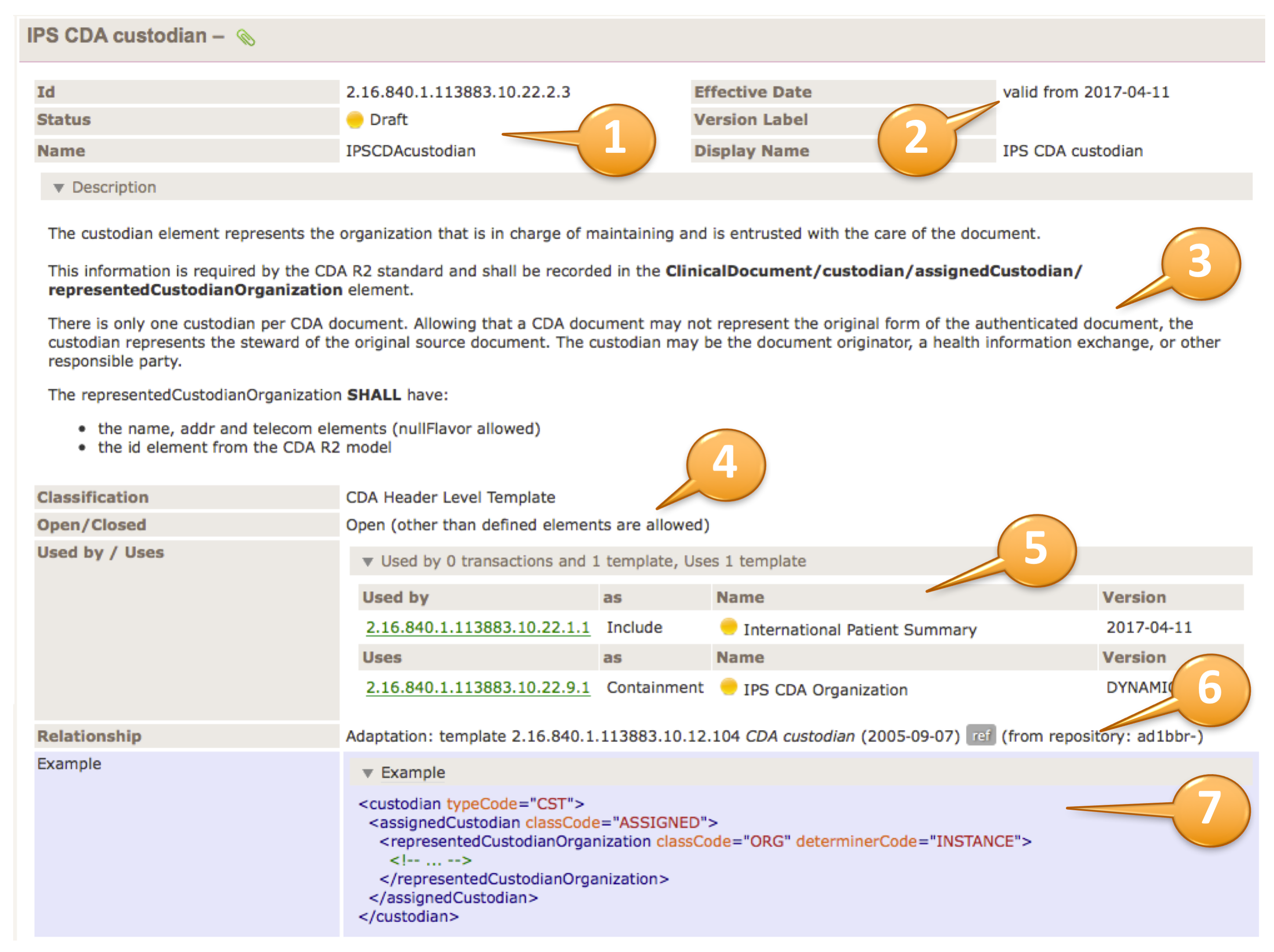

Reading Publication Artifacts

A reading guide is available that explains the formalism used to express the publication artifacts, i.e. template meta data and template design. For convenience the guide is included in the appendix. (see section 12 How to read the table view for templates)

Technical Background

What is a CDA

CDA R2 is "… a document markup standard that specifies the structure and semantics of clinical documents for the purpose of exchange” [CDA R2, Section 1.1]. Clinical documents, according to CDA, have the following characteristics:

- Persistence

- Stewardship

- Potential for authentication

- Context

- Wholeness

- Human readability

CDA defines a header for classification and management and a document body that carries the clinical record. While the header metadata are prescriptive and designed for consistency across all instances, the body is highly generic, leaving the designation of semantic requirements to implementation.

Templated CDA

CDA R2 can be constrained by mechanisms defined in the “Refinement and Localization” section of the HL7 Version 3 Interoperability Standards. The mechanism most commonly used to constrain CDA is referred to as “templated CDA”. This specification created a set of artifacts containing modular CDA templates (and associated value sets) for the purpose of the International Patient Summary, and the templates can be reused across any number of CDA document types.

There are different kinds of templates that might be created. Among them, the most common ones are:

- CDA Document Level Templates constrain fields in the Clinical Document Architecture (CDA) header, and define containment relationships to CDA sections.

For example, a History-and-Physical document-level template might require that the patient’s name be present, and that the document contain a Physical Exam section. - CDA Header Level Templates constrain fields for parts of the CDA header, like the patient (record target), the author, participations or the service event.

- CDA Section Level Templates constrain fields in the CDA section, and define containment relationships to CDA entries.

For example, a Physical-exam section-level template might require that the section/code be fixed to a particular LOINC code, and that the section contain a Systolic Blood Pressure observation. - CDA Entry Level Templates constrain the CDA clinical statement model in accordance with real world observations and acts.

For example, a Systolic-blood-pressure entry-level template defines how the CDA Observation class is constrained (how to populate observation/code, how to populate observation/value, etc.) to represent the notion of a systolic blood pressure.

Open and Closed Templates

Open templates permit anything to be done in the underlying standard that is not explicitly prohibited. This allows templates to be built up over time that extend and go beyond the original use cases for which they were originally designed.

Closed templates only permit what has been defined in the template, and do not permit anything beyond that. There are good reasons to use closed templates, sometimes having to do with local policy. For example, in communicating information from a healthcare provider to an insurance company, some information may need to be omitted to ensure patient privacy laws are followed. Most templates developed for CDA are of the open sort.

Template versioning

Template versioning is needed to enable template designs to evolve over time.

Template versioning enables template designers to control and shape the conformance statements that make up a template’s design over time tailoring the design to fit the template’s intended purpose.

Each template version is associated with a particular template. The template – as a whole – has a mandatory globally unique, non-semantic, identifier. The identifier serves as the identifier of the original intent of the template and as the identifier of the set of versions that represent the template over time.

Template versions have a mandatory timestamp (date and optional time), called the “effective date”. The date can be seen as the point in time when the template version “came into being”, i.e. was recognized as existent by the governance group. Use of the template prior to this date would be considered an invalid use of the template.

For further information on Templates, Template Versions and related topics refer to the HL7 Templates Standard[8].

Conformance Verbs

The conformance verb keywords SHALL, SHOULD, MAY and SHALL NOT in this document are to be interpreted as described in the HL7 Version 3 Publishing Facilitator's Guide[15].

- SHALL: an absolute requirement

- SHALL NOT: an absolute prohibition against inclusion

- SHOULD: best practice or recommendation. There may be valid reasons to ignore an item, but the full implications must be understood and carefully weighed before choosing a different course

- MAY: truly optional; can be included or omitted as the author decides with no implications

Identifiers for Templates and Value Sets

This specification uses the following OIDs for the artifacts that are registered at the HL7 OID registry.

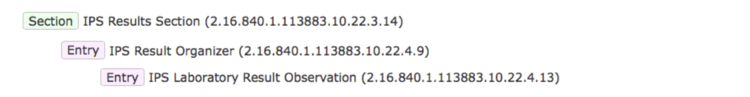

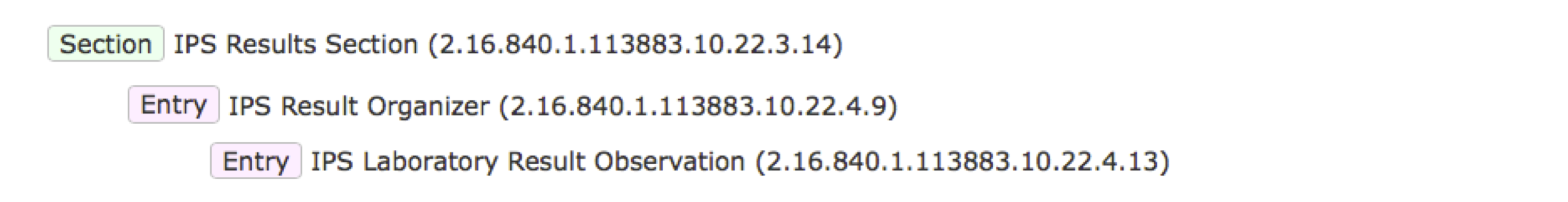

- The root OID for templates is 2.16.840.1.113883.10.22

- Document Level Templates are sub branch .1, e.g. 2.16.840.1.113883.10.22.1.1 International Patient Summary

- Header Level Templates are summarized under 2.16.840.1.113883.10.22.2, e.g. 2.16.840.1.113883.10.22.2.1 IPS CDA recordTarget

- Section Level Templates are summarized under 2.16.840.1.113883.10.22.3, e.g. 2.16.840.1.113883.10.22.3.1 IPS Medication Summary Section

- Entry Level templates are summarized under 2.16.840.1.113883.10.22.4, e.g. 2.16.840.1.113883.10.22.4.19 IPS Certainty Observation

- “other” assistance templates are summarized under 2.16.840.1.113883.10.22.9, e.g. 2.16.840.1.113883.10.22.9.2 IPS CDA Device

- The root OID for Value Sets is 2.16.840.1.113883.11

The sub branches for templates follow the recommendations of HL7 International and ISO 13582[16]

Terminologies

Note: Much of the description provided in this section is copied and adapted from the §4.2.8 Vocabulary Conformance section of the C-CDA DSTU R2.1 Implementation Guide Volume 1.[17]

The templates in this document use terms from several code systems. These vocabularies are defined in various supporting specifications and may be maintained by other bodies, as is the case for the LOINC® and SNOMED CT® vocabularies. The primary terminologies identified for this specification are listed in section 4.1.

Note that value set identifiers (e.g., ValueSet 2.16.840.1.113883.1.11.78 Observation Interpretation (DYNAMIC)) used in the binding definitions of template conformance statements do not appear in the XML instance of a CDA document. The definition of the template must be referenced to determine or validate the vocabulary conformance requirements of the template.

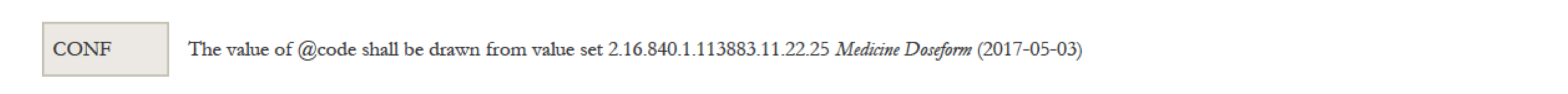

Value set bindings adhere to HL7 Vocabulary Working Group best practices, and include both an indication of stability and of coding strength for the binding. Value set bindings can be STATIC, meaning that they bind to a specified version of a value set, or DYNAMIC, meaning that they bind to the most current version of the value set. If a STATIC binding is specified, a date SHALL be included to indicate the value set version. If a DYNAMIC binding is specified, the value set authority and link to the base definition of the value set SHALL be included, if available, so implementers can access the current version of the value set. When a vocabulary binding binds to a single code, the stability of the binding is implicitly STATIC.

For example, to convey @code=11450-4, the code’s displayName 'Problem List', the OID of the codeSystem from which the code is drawn '2.16.840.1.113883.6.1', and the codeSystemName 'LOINC', the tabular view used in this guide is presented as shown below.

| hl7:code | 1 … 1 | M | |||

| @code | CONF | 1 … 1 | F | 11450-4 | |

| @codeSystem | 1 … 1 | F | 2.16.840.1.113883.6.1 (LOINC) | ||

| @displayName | 1 … 1 | F | Problem List | ||

[Figure 5] Binding to a Single Code (tabular view)

HL7 Data Types Release 1 requires the codeSystem attribute unless the underlying data type is “Coded Simple” or “CS”, in which case it is prohibited. The displayName and the codeSystemName are optional, but recommended, in all cases.

The above example would be properly expressed as follows.

<code code="11450-4" codeSystem="2.16.840.1.113883.6.1"/>

<!-- or -->

<code code="11450-4" codeSystem="2.16.840.1.113883.6.1"

displayName="Problem List" codeSystemName=”LOINC”/>

[Figure 6] XML Expression of a Single-Code Binding

A full discussion of the representation of vocabulary is outside the scope of this document; for more information, see the HL7 V3 Normative Edition 2010[18] sections on Abstract Data Types and XML Data Types R1.

There is a discrepancy between the HL7 R1 Data Types and this guide in the implementation of translation code versus the original code. The R1 data type requires the original code in the root. The convention agreed upon for this implementation guide is that a code from the required value set is used in the element and other codes not included in the value set are to be represented in a translation for the element. Note: This discrepancy is resolved in HL7 Data Types R2, but that is not available for use in CDA R2.

In the next example, the conformant code is SNOMED CT code 206525008.

<code code="206525008" codeSystem="2.16.840.1.113883.6.96"

displayName="neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis" codeSystemName="SNOMED CT">

<translation code="NEC-1" codeSystem="2.16.840.1.113883.19"

displayName="necrotizing enterocolitis"/>

</code>

[Figure 7] Translation Code Example

Value set tables are present below a template, or are referenced if they occur elsewhere in the specification, when there are value set bindings in the template. The value set table provides the value set identifier, a description, and a link to the source of the value set when possible. Ellipses in the last row indicate the value set members shown are examples and the true source must be accessed to see all members.

If a value set binding has a DYNAMIC stability, implementers creating a CDA document must go to the location in the URL to check for the most current version of the value set expansion.

Note: Much of the description provided in the following three sections on value set definitions and expansions and extending value sets is adapted from Core Principles and Properties of HL7 Version 3 Models.[19]

Value Set Definitions

Two approaches can be used to define the contents of a Value Set:

- Extensional Definition: Explicitly enumerating each of the Value Set concepts.

- An Extensional Definition is an enumeration of all of the concepts within the Value Set. A Value Set defined by extension is composed of explicitly enumerated sets of concept representations (with the Code System in which they are valid). The simplest case is when the Value Set consists of only one concept.

- Intensional Definition: Defining an algorithm that, when executed by a machine (or interpreted by a human being), yields an enumeration of all of the concepts within the Value Set, which is called a Value Set Expansion.

- An Intensional Definition is a set of rules that can be expanded (ideally computationally) to an exact set of concept representations at a particular point in time.

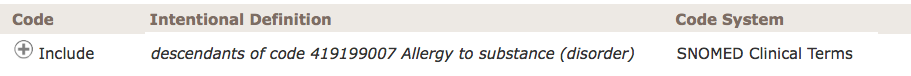

Many of the value sets used in the IPS specification are defined intensionally. The source of truth for these value sets and their definitions for IPS is ART-DECOR®[20].

[Figure 8] Intensional value set definition.

Value Set Expansions

To obtain a list of enumerated concepts, Value Sets must be expanded. This means that the Value Set Definition must be converted to a list of concept representations at a point in time. This normally is a list of codes that may be used in populating or validating communicated model instances (but it may alternatively be a list of designations). While this is straightforward for extensional Value Set Definitions, an intensional Value Set Definition must be resolved to a Value Set Expansion by processing the rules contained in the Value Set Definition. Value Set Expansion can be done as early as the point of Value Set definition or as late as run time. For intensional Value Sets, the set of concepts contained in the expansion will generally change when the definition is changed (a new version of the Value Set Definition), but also may change with the identical version of the definition if the underlying code systems change, and the changes are part of the Value Set Expansion. This can be controlled if the definition statement refers to specific code system versions, thereby prohibiting the expansion from changing when the code system changes with a new version release. See Core Principles and Properties of HL7 Version 3 Models for additional details.[19]

In order to implement the IPS specification, the intensionally defined value sets must be expanded (as noted above). ART-DECOR® is expected to provide capabilities for generating the required value set expansions. Other terminology servers are also expected to provide this service.

How to extend Value Sets

For elements with a binding to a value set that allows extensibility (Extensible/CWE), it may at times be necessary to extend the value set in order to support implementation needs. Coded With Extensibility (Extensible/CWE) means that the set of codes resulting from processing the Value Set Definition is not necessarily complete for its intended use-case. There may be some concepts that need to be communicated that cannot be represented within the expansion of the specified value set. In these cases, implementers therefore have permission to send local codes or original text within the coded element if an appropriate code cannot be found within the value set and its current expansion. When this does occur, however, there is an expectation that implementers should feed back these "missing concepts" to the maintainers of the Value Sets or referenced Code System(s) to have the necessary concept added, and then to transition to the new "official" code when one is subsequently added to the value set.

Functional requirements and high-level use cases

Several use cases may be identified for the International Patient Summary within its scope (“specialty-agnostic, condition-independent, but readily usable by clinicians for the cross-border unscheduled care”). Section Examples provide a subset of some real world user stories for the cross-border care developed by the Trillium Bridge Project and by the S&I EU-US eHealth Cooperation Initiative in the scope of the EU/US Roadmap initiative.

The cross-border care is not however the only expected usage scenario for the IPS. Some European countries have already manifested their interest on the IPS work for their future national Patient Summary for unscheduled care. Patient summary initiatives are currently in various stages of development in other parts of the world.

As shown by the user stories there are several possible options in terms of creation, sharing and usage of an IPS. For example:

- An IPS can be created when requested and used before, during, or after a care episode; or can be asynchronously generated and made available for future usage (e.g. store and retrieve).

- The IPS can be retrieved using a document exchange infrastructure; transported by the patient; or shared using cloud-services.

- The IPS may be subject of a transformation process that may include syntactical conversions, coded concept mappings and coded concept designation or free text translations. This transformation process may be performed in the creation phase, during the transmission, or after the IPS has been received, possibly using an external service.

- Finally, the received CDA may be used in different ways. For example, displayed using a common CDA stylesheet; display the extracted relevant information; incorporated into the receiver’s EHR. Alternatively, a specialized viewer may be adopted to enable the display of the translated content.

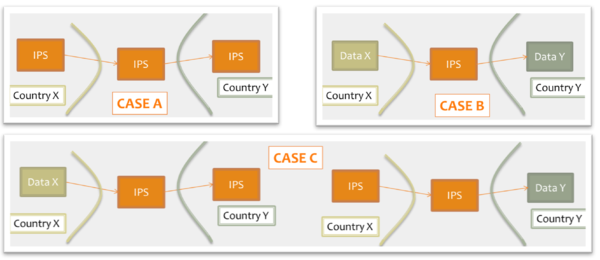

Moreover for cross-jurisdiction exchange, the IPS could be used as:

- shared format among jurisdictions (case A), where jurisdictions originate and use IPS conforming documents unaltered.

- pivot document among existing summaries / data formats (case B). For example, the IPS is used as intermediate format between the US C-CDA CCD (please note that the CCD scope differs from that of the IPS) and the European eHDSI Patient Summary for a Transatlantic Patient Summary exchange.

- mixed mode (Case C), where either the originator or the consumer is expected to use an IPS conforming document.

[Figure 9] Examples of IPS usage

Considering all those possible combinations and additional business requirements agreed by jurisdictions, there are several technical infrastructures and services that may be designed to support these requirements.

It is out of scope of this standard to provide any indication about solutions and strategies for the IPS creation, sharing, syntactical and semantic mapping, translation, and use.

That said, an International Patient Summary may:

- be the result of automatic assembly (assembled IPS) or of a human summarization act (human curated IPS)

- have one or more EHR sources

- document information from a single or multiple jurisdictions/organizations

- aggregate input from a single or multiple encounters.

A clear determination of such contextual information raises the trustworthiness of the received IPS and helps the appropriate usage of its content by the receiver . Most of these aspects are related to data provenance introduced in section 1.8 and further detailed in section 4.11.

Even if many jurisdictions require that only one active Patient Summary for unscheduled care be made available, this guide does not impose such constraints and leaves them to jurisdictional implementations.

Moreover it is also out of scope of this guide to:

- provide guidance on how to determine the relevance of data for their inclusion in a IPS;

- define selection or composition rules for facing potential inconsistencies from multiple sources in case of automatic collection.

Code mappings and multilingual support

The capability of managing locally used coded concepts and reference terminologies, and that of providing receiving providers with human readable information in a language that can be understood by them, are critical aspects to be taken in account in the cross-border sharing of documents. This section summarizes some of the requirements related to these aspects, including also additional needs derived from the European cross-border services and some lessons learned by the EU/US Trillium Bridge Project.

The European cross-border services (eHDSI) use a business to business exchange infrastructure based on a network of country gateways that mediate access to the national infrastructures. The eHDSI Patient Summary (eHDSI PS) is used as a “pivot” document for the cross-border exchange. Local PS using data/document formats are in fact remapped into the eHDSI PS. The document exchanged is processed each time it passes through one of these gateway applying the needed syntactical transformation, code mappings. and translation of the code designations. Finally, in the current practice the received PSs are displayed using specialized display tools that build a human readable representation of the PS in the target language using the translated designations reported in the coded entries.

The adoption of translated narratives in the received document has been one of the indications received by the Trillium Bridge Project. This in fact allows extending multilingual support for the cross-border patient summaries to a wider set of potential consumers (EHR-or PHR systems), without requiring specialized viewers as applied in the eHDSI services.

Concept code mapping

In several real world use cases the records used as source for the Patient Summaries may use locally adopted terminologies, which are mapped to the reference value sets when possible, or otherwise used directly to provide uncoded information. This leads to a series of requirements listed below and detailed further in section 4 Design conventions and principles.

- When the original coded concept is mapped to one of the coded concepts included in the reference value sets (called hereafter reference code/coded concept), both the original and the reference codes SHALL be reported in the IPS instance.

- When the original coded concept is not mapped to one of the coded concepts included in the reference value sets, the original code SHALL be reported in the IPS instance as well as the indication that mapping was not successful.

- When the original record, for a specific coded element, is not able to provide coded but only textual information, this information SHALL be reported in the IPS instance.

This guide also accommodates these situations:

- The original record may support multi-coding. The IPS instance should make clear whether the additional codes belong to the original content or are the result of post hoc concept code mapping.

- The original record may include references to the pieces of text the coding was derived from. If present, the IPS instance should preserve this link between the original code and the referred text.

- Distinct original and reference coded concepts may belong to the same code system. This may be the result of a different level of granularity between the original and the reference value sets, or the result of format transformation - e.g. CCD document is used as input for generating an IPS. The requirement of recording both coded concepts applies also to these cases.

Multilingual support

Multilingual support by IPS can be split in two categories of action:

- The translation of coded concept designations (displayName)

- The translation of the narrative.

These actions may deal with various choices:

- Translation to the language of the receiving care provider: a foreign provider retrieves a translated copy of the IPS from the patient's country of affiliation…

- Translation to a commonly agreed language: an English version of the IPS is prepared.

- Predefined set of translations included in the shared IPS.

This guide does not favor any of these solutions. All of them are supported.

Translation of Designations

The European Cross-border services requires that for “safety and liability reasons” all of the original coded terms (designations, displayName) shall be recorded in the exchanged documents together with at least the English and the receiving country language terms (designations, displayName) associated with the reference codes. The designations translated in the receiving country language are used to generate the human readable content shown to the receiving provider. No free text translation is applied in this case. In order to accomplish this objective, the IPS should have the capability to record one or more designations, possibly indicating the language used. The solution chosen to fulfill this requirement is specified in section 4.6.

Narrative Translation

Narrative translation covers two kinds of operations:

- Translation of the original narrative text, which can be automated (e.g. using translation services) and/or human curated.

- Creation of new narrative for the target language, based on the coded entries.

The level of quality and liability obtained depends on the solution adopted and on the quality of the translation service used. It is out of the scope of this guide to suggest any of these solutions. In all cases, however:

- the language of the narrative should be identifiable

- the original and the translated narrative should be clearly distinguished

- the translation methodology applied (e.g. derived from the coded entries; translated by a generic service;..) should be noted

Design conventions and principles

How to use terminologies (preferred binding)

As stated in section 1.5, to be universally exchangeable the International Patient Summary must rely on international multilingual reference terminologies. To that effect, each codeable element of the international patient summary template is bound to a Value Set built upon an international reference terminology, such as SNOMED CT, LOINC, UCUM or EDQM Standard Terms. In some selected cases, in consideration of the availability of other globally usable reference terminologies and for alignment with a future FHIR version of the IPS, FHIR-defined terminologies have been specified. These terminologies have been selected to provide the preferred bindings for the codeable elements of the patient summary. They are the primary terminologies of this specification.

Nevertheless, it is anticipated that in some situations a system producing an instance of patient summary might not support one or the other of these primary terminologies, supporting only a local interface terminology instead. Similarly, it is also anticipated that the receiving system might in some cases not be able to use a code in a patient summary, either because this code belongs to a primary terminology that the receiving system does not support or because this code belongs to an interface terminology specific to the country of the producing system.

In order to maximize the international scope and usability of patient summaries, and also to accommodate the exceptional situations listed above, this specification makes these requirements:

- The Primary Code of a codeable element SHOULD be populated.

- If populated, the Primary Code of a codeable element SHALL be chosen from the primary terminology assigned to the value set bound to this element; unless exceptions have been agreed.

- The 'displayName' of the Primary Code SHALL be populated with a term representing this same code in the terminology used, in the language chosen for the current instance of the patient summary.

- When the primary 'code' element is not populated, an appropriate 'nullFlavor' value SHALL be used along with the 'originalText' element (referencing a textual expression in the narrative representing the meaning for the producer) and/or one or more coded 'translation' elements.

- One or more Alternate Codes from a local interface terminology MAY be provided, each with its associated 'displayName'.

- In case the primary code is derived from an alternate terminology the alternate code SHOULD be provided in the translation element.

Primary Code

In the data type for codeable elements (CD constrained by the CD.IPS template), the Primary Code is represented by the attributes @code, @displayName, @codeSystem, @codeSystemName, @codeSystemVersion.

Alternate Code

In the data type for codeable elements (CD constrained by the CD.IPS template), an Alternate Code is carried in a 'translation' sub-element.

Original Text

In the data type for codeable elements (CD constrained by the CD.IPS template), the Original Text is provided in the 'originalText' sub-element.

Representing "known absent" and "not known"

In line with the properties of minimalism and non-exhaustiveness for the IPS (see the IPS definition above), and benefiting from the experience acquired with the European cross-border services, this guide explicitly addresses two general situations:

- condition or activity unknown

- condition or activity known absent.

Other kinds of negations such as: (a) the negation of an allergy to a specific agent; (b) the absence of a particular disease; or (c) the fact that a specific vaccination has not been performed, have been considered beyond the set of essential data for an IPS.

This specification represents this core set of negations (“general condition/activity unknown” and “general condition/activity/known absent” ) using explicit coded elements rather than relying on specific mechanisms of HL7 CDA such as nullFlavor and negationInd attributes or human readable text (possibly not understood by the foreign country receiver).

In contrast to the practice to use negationInd or nullFlavor attributes on a section itself, we prohibit the use of these attributes on section level to express “unknown” or “no information” situations. A section holds the categorized (coded) narrative part of the documented activity and will never carry negationInd or nullFlavor attributes. Instead, we enforce by design, that “unknown” or “no information” expressions always go to the coded entry with a corresponding act code.

The main reasons for this choice are:

- @negationInd in CDA has been superseded in V3 later by two other negation indicators: @actNegationInd and @valueNegationInd.

- To make clinical content representation less dependent on a particular format or syntax, enabling a more practical path to transforming and exchanging data from one standard format (e.g. CDA R2) to another (e.g. FHIR).

- to provide one single method to express the presence or absence of a particular condition (e.g. an allergy) or activity (e.g. an immunization), or the lack of knowledge regarding this kind of condition or activity, resulting in a more robust and easily implementable specification.

For the other kinds of negations, not explicitly mentioned in this guide, it is suggested to apply – where possible – the same approach. Future versions of this guide may extend the number of cases covered and include new coded concepts for supporting them.

When needed, more specific statements such as the absence of a specific condition or activity, although considered as beyond the set of essential data for IPS, can still be expressed by using the native negationInd attribute of CDA R2.

Uncoded information

An IPS originator may not be able to value a coded element with an appropriate coded concept, but only with textual information. This may happen for two reasons:

- the originator is not able to express the concept in the reference value sets

- the originator is not able to express the concept in any known terminology.

The first case, assuming that the coding strength is Required (aka CNE, coded, no extensions), is represented in this guide with the following assertion:

<code codeSystem="2.16.840.1.113883.6.96" nullFlavor="OTH">

<originalText>

<reference value="#ref1"/>

</originalText>

</code>

That is expressing that there are no codes applicable in the referred code system (in the example, SNOMED CT). Please note that according to this guide the text is documented in the section narrative and only referenced by the coded element.

Note: Data Types R1 doesn't allow specifying that there are no codes applicable in the referred value set, as instead is possible with Data Types R2. Future versions of this guide may consider extending the data type to better support this situation.

The second case, that applies both to Required (aka CNE, coded no extensions) and Extensible (CWE, coded with extensions) coding strengths, is instead here represented valuing the coded element with the most generic nullFlavor “NI” (No Information) and pointing the text in the section narrative:

<value xsi:type="CD" nullFlavor="NI">

<originalText>

<reference value="#ref1"/>

</originalText>

</value>

Note: The most proper NullFlavor code to be used here would be "UNC" (Uncoded). This code is available in the current and other recent versions of the HL7 RIM, but it is not present in version 2.07 of the RIM on which the CDA R2 standard is based. In the absence of "UNC", the most appropriate NullFlavor code to use for representing that the data is unable to be coded is "NI".

Unmapped Coded Concepts

In several real world situations the records used as source for the Patient Summaries may use locally adopted terminologies mapped into the reference value sets. When the original coded concept cannot be mapped in one of the coded concepts included in the reference value sets, it is recommended to populate the original code in the IPS instance (in a 'translation' sub-element), with a nullFlavor indicating that the mapping didn’t occur. (See also the Concept code mapping in the functional requirements section.). The nullFlavor value depends upon the coding strength of the binding.

Two circumstances are considered here: the case in which the coding strength is Required (CNE) and when it is Extensible (CWE).

In the case of coding strength Required (CNE), use nullFlavor "OTH":

<value xsi:type="CD" codeSystem="2.16.840.1.113883.6.96" nullFlavor="OTH">

[

<originalText>

<reference value="#ref1"/>

</originalText>

]

<translation code="A02.9" codeSystem="2.16.840.1.113883.6.3"

displayName="Infezioni da Salmonella non specificate"/>

</value>

The square brackets [ ] are used to indicate that the originalText element may or may not be present

Note: It may happen that a mapping would be possible in the target code system, but not in the target value set; Data Types R1 does not allow the specification of this difference, that there are no codes applicable in the reference value set, which is possible with Data Types R2.

Future versions of this guide may consider extending the data type to better support this situation.

In the case of Extensible (CWE) coding strength, this guide recommends representing the original code in the <translation> sub-element and using a nullFlavor for the primary code. This highlights the fact that a mapping to the reference value set was attempted, but no suitable target codes were identified.

<value xsi:type="CD" codeSystem="2.16.840.1.113883.6.96" nullFlavor="NI">

[

<originalText>

<reference value="#ref1"/>

</originalText>

]

<translation code="A02.9" codeSystem="2.16.840.1.113883.6.3"

displayName="Infezioni da Salmonella non specificate"/>

</value>

The square brackets [ ] are used to indicate that the originalText element may or may not be present.

Mapped coded concepts

As mentioned above, in several circumstances an original coded concept is mapped into the reference value set. When this occurs, both the original and the reference codes should be reported in the IPS instance.

Functional requirements exposed in section 3.1 (multi-coding, link to original text, mapping between codes of the same code system) are also detailed below.

Case 1: Single local code mapped to primary code from the reference value set.

<value xsi:type="CD" code="42338000" codeSystem="2.16.840.1.113883.6.96"

displayName="Salmonella gastroenteritis">

[

<originalText>

<reference value="#ref1"/>

</originalText>

]

<translation code="003.0" codeSystem="2.16.840.1.113883.6.103"

displayName="Gastroenterite da Salmonella"/>

</value>

The square brackets [ ] are used to indicate that the originalText element may or may not be present

Case 2: Multiple local codes mapped together using nested 'translation' elements, and mapped to the primary code from the reference value set.

<value xsi:type="CD" code="422479008" codeSystem="2.16.840.1.113883.6.96"

codeSystemName="SNOMED CT"

displayName="FEMALE BREAST INFILTRATING DUCTAL CARCINOMA, STAGE 2">

[

<originalText>

<reference value="#problem4name"/>

</originalText>

]

<translation code="code-example" codeSystem="1.999.999"

codeSystemName="this is only an example"

displayName="FEMALE BREAST INFILTRATING DUCTAL CARCINOMA, STAGE 2">

<translation code="174.9" codeSystem="2.16.840.1.113883.6.103"

codeSystemName="ICD-9CM"

displayName="Malignant neoplasm of breast (female), unspecified"/>

<translation code="C50.919" codeSystem="2.16.840.1.113883.6.90"

codeSystemName="ICD-10-CM"

displayName="Malignant neoplasm of unspecified site of unspecified female breast"/>

</translation>

</value>

Case 3: Original and the reference coded concepts belong to the same code system (distinct codes). This may be the result of a different level of granularity between the original term and the reference value sets.

<code code="60591-5" codeSystem="2.16.840.1.113883.6.1"

codeSystemName="LOINC" displayName="Patient Summary">

<translation code="60592-3" codeSystem="2.16.840.1.113883.6.1"

displayName="Patient summary unexpected contact"/>

</code>

Note: The R1 data type definition identifies the <translation> as “a set of other concept descriptors that translate this concept descriptor into other code systems." There is however a common understanding that it may be more than one representation in a single code system where code systems allow multiple representations, such as SNOMED CT. Data Types R2 extended the possibility to provide translations also in the same code system.

Translation of designations

The capability of recording one or more designations, in different languages, for the exchanged Patent Summary is one of the functional requirements requested for “safety and liability reasons” by the European Cross-border services (see Designations’ Translation under the Functional requirements and high-level use cases for more details).

Given that the base CDA R2 standard which uses datatypes R1 does not offer a native way to convey the language translation of 'displayName', this guide introduces an optional 'ips:designation' extension to the CD datatype for that purpose.

Below are examples of usage of this extension.

No code mapping

<code code="60591-5" codeSystem="2.16.840.1.113883.6.1"

codeSystemName="LOINC" displayName="Patient Summary">

<ips:designation language="it-IT">Profilo Sanitario Sintetico</ips:designation>

<ips:designation language="fr-FR">Patient Summary</ips:designation>

<ips:designation language="en">Patient Summary</ips:designation>

</code>

Including code mapping

<value xsi:type="CD" code="42338000" codeSystem="2.16.840.1.113883.6.96"

displayName="Salmonella-gastroenterit">

<ips:designation language="da-DK">Salmonella-gastroenterit</ips:designation>

<ips:designation language="en">Salmonella gastroenteritis (disorder)</ips:designation>

[

<originalText>

<reference value="#ref1"/>

</originalText>

]

<translation code="003.0" codeSystem="2.16.840.1.113883.6.103"

displayName="Gastroenterite da Salmonella"/>

</value>

Narrative Translations

“Narrative translation” means both the translation of the original narrative text, that can be human curated or automatically performed, and the generation of a translated narrative based on the coded entries.

The functional requirements associated with this process are described in the Designations’ Translation section under Functional requirements and high-level use cases, and can be summarized in two main points : (a) language identification and (b) distinguishable original and translated narratives. Moreover, the methodology applied for the narrative translation (e.g. derived from the coded entries; translated by a generic service;..) should be noted.

Regarding the translation of section narrative <text>, this guide recommends providing this translation on purely textual subordinate sections (one per translation) as specified in the IPS Translation Section (2.16.840.1.113883.10.22.3.15) template.

An example of this is:

<section>

<templateId root="2.16.840.1.113883.3.1937.777.13.10.5"/>

<id root="..." extension="..."/>

<code code="48765-2" codeSystem="2.16.840.1.113883.6.1"

displayName="Allergies and adverse reactions"/>

<title>Allergies and Intolerances</title>

<text>No known Allergies</text>

<!-- omissions -->

<component>

<section>

<!-- subordinate section carrying a translation of the parent section -->

<title>Allergie ed Intolleranze</title>

<text>Nessuna Allergia Nota</text>

<languageCode code="it-IT"/>

</section>

</component>

</section>

Determining the Status of Clinical Statement

Note: Most of the description provided in this section is copied from the § 3.3 Determining the Status of Clinical Statement of the C-CDA DSTU R2.1 Implementation Guide Volume 1.[17]

A recipient must be able to determine whether the status of an entry — which can include a problem, a medication administration, etc. — is active, completed, or in some other state. Determination of the exact status is dependent on the interplay between an act’s various components (such as statusCode and effectiveTime). The following principles apply when representing or interpreting the status of a clinical statement.

- The Act.statusCode of the clinical statement specifies the state of the entry: Per the RIM, the statusCode “reflects the state of the activity. In the case of an Observation, this is the status of the activity of observing, not the status of what is being observed.”

- Act.statusCode and Act.moodCode are inter-related: Generally, an act in EVN (event) mood is a discrete event (a user looks, listens, measures, and records what was done or observed), so generally an act in EVN mood will have a statusCode of “completed.” A prolonged period of observation is an exception, in which a user would potentially have an observation in EVN mood that is “active.” For an Observation in RQO (request) mood, the statusCode generally remains “active” until the request is complete, at which time the statusCode changes to “completed.” For an Observation in GOL (goal) mood, the statusCode generally remains “active” as long as the observation in question is still an active goal for the patient.

- Act.statusCode and Act.effectiveTime are interrelated: Per the RIM, the effectiveTime, also referred to as the “biologically relevant time,” is the time at which the act holds for the patient. So, whereas the effectiveTime is the biologically relevant time, the statusCode is the state of the activity. For a provider seeing a patient in a clinic and observing a history of heart attack that occurred 5 years ago, the status of the observation is completed, and the effectiveTime is five years ago.

The IPS Problem Concern Entry and the IPS Allergy and Intolerance Concern templates reflect an ongoing concern on behalf of the provider that placed the concern (e.g. a disease, an allergy, or other conditions) on a patient’s problem or allergy list. The purpose of the concern act is that of supporting the tracking of a problem or a condition (e.g. an allergy). A concern act can contain one or more discrete observations related to this concern. Each of them reflects the change in the clinical understanding of a condition over time. For instance, a Concern may initially contain a symptom of “chest pain”, later identified as consequence of a gastroesophageal reflux. The later problem observation will have a more recent author time stamp.

There are different kinds of status that could be of clinical interest for a condition:

- The status of the concern (active, inactive,..)

- The status of the condition (e.g. active, inactive, resolved,..)

- The confirmation status [verification status, certainty] (e.g. confirmed, provisional, refuted,…)

Not all of them can be represented in a CDA using the statusCode elements of the concern (ACT) and observation (condition).

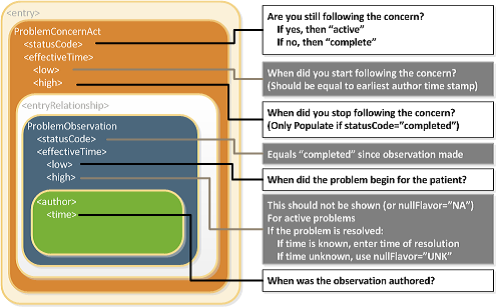

Status of the concern and related times

The statusCode of the Problem Concern Act is the definitive indication of the status of the concern. So long as the provider has an ongoing concern — meaning that the provider is monitoring the condition, whether it includes problems that have been resolved or not — the statusCode of the Concern Act is “active.” When the underlying conditions are no longer an active concern, the statusCode of the Problem Concern Act is set to “completed.”

The Concern Act effectiveTime reflects the time that the underlying condition was considered a concern. It may or may not correspond to the effectiveTime of the condition (e.g., even five years later, the clinician may remain concerned about a prior heart attack). The effectiveTime/low of the Concern Act asserts when the concern became active. This equates to the time the concern was authored in the patient's chart. (i.e. it should be equal to the earliest author time stamp) The effectiveTime/high asserts when the concern became inactive, and it is present if the statusCode of the concern act is "completed". If this date is not known, then effectiveTime/high will be present with a nullFlavor of "UNK".

Status of the condition and related times

Each Observation contained by a Concern Act is a discrete observation of a condition. Its statusCode is always “completed” since it is the “status of the activity of observing, not the status of what is being observed”. The clinical status of a condition (e.g. a disease, an allergy,..) is instead recorded by specialized subordinated observations (IPS Allergy Status Observation; IPS Problem Status Observation), documenting whether it is active, in remission, resolved, et cetera. The effectiveTime, also referred to as the "biologically relevant time", is the time at which the observation holds for the patient. For a provider seeing a patient in the clinic today, observing a history of penicillin allergy that developed six months ago, the effectiveTime is six months ago. The effectiveTime of the Observation gives an indication of whether or not the underlying condition is resolved, but the current status is documented by a subordinated observation. The effectiveTime/low (a.k.a. "onset date") asserts when the allergy/intolerance became biologically active. The effectiveTime/high (a.k.a. "resolution date") asserts when the allergy/intolerance was biologically resolved. If the date of resolution is not known, then effectiveTime/high will be present with a nullFlavor of "UNK".

[Figure 10] Problem Concern Act (from C-CDA IG DTSU R2.1)[17]

Confirmation status

The confirmation status, also noted as verification status or certainty, indicates the certainty associated with a condition (e.g. confirmed, provisional, refuted,…) providing information about the potential risk, for example, of a reaction to the identified substance. The confirmation status of a condition (e.g. a disease, an allergy,..) is recorded by a specialized subordinated observation (IPS certainty Observation), documenting whether the condition is confirmed, unconfirmed, provisional, refuted, et cetera.

The use of medication statements in the summary

A medication list may strongly vary depending on the context of use (e.g. support for prescription or dispensation, drug reconciliation, etc. ) and on the type of information reported (e.g. patient-reported medication, prescribed, dispensed or administered medications, active or past medications, etc.).

This is still true also for the medication summary in a Patient Summary. It could be, for instance, a list of "Relevant prescribed medicines whose period of time indicated for the treatment has not yet expired whether it has been dispensed or not" (European guidelines on Patient Summary [21]); a list of actually dispensed medications; a list of relevant medications for the patient (IHE PCC [22]); or conversely, it could be a complete history including the full patient's prescription and dispensation history and information about intended drug monitoring (C-CDA [17]).

Moreover, for the scope of the International Patient Summary, it is important to know what medications are being taken by or have been given to a patient; without necessarily providing all the details about the medication order, supply, administration or monitoring. This information need, in line with the IPS principle of minimum non exhaustive data, is well expressed by the concept of Medication Statement (see https://www.hl7.org/fhir/medicationstatement.html).

The IPS medication summary is therefore a list of relevant medication statements, possibly built from either a prescription list or a dispensation list. In fact, in many practical cases data included in a Patient Summary are derived from the list of the medicines prescribed by a GP and recorded in its EHR-S; or extracted from a in regional/national prescribing and/or dispensation systems. In these cases, data obtained from actual dispensation and/or prescription records can be still recorded in the IPS as statements and the original request, supply or administration records referred by the statement if really needed.

Medicinal Product Identification

The identification of medicinal products is quite easily solved within a single jurisdiction relying on local drug databases. In contrast, it is one of the major open issues for eHealth services across jurisdictions.

The set of ISO standards called IDMP[23] - designed initially for the regulatory scope, but hopefully extensible to other domains - are the most promising solution for solving this known issue, as also highlighted by the European project OpenMedicine [24]. The completion of the IDMP implementation guides, the deployment of the needed supporting services, and the development of some companion standards that will allow the seamless flow of the IDMP identifiers and attributes from the regulatory space to the clinical world (and back) are however still in progress. Additional time is needed before these identifiers and attributes will be available in full for practical use.

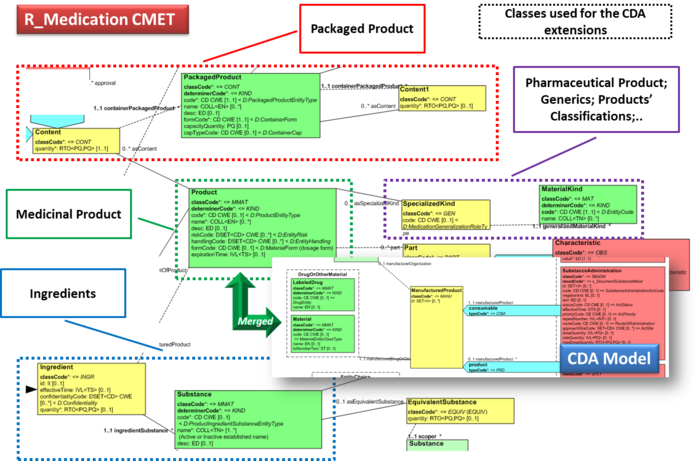

Following therefore the IPS principles of “implementability”, “openness" and "extensibility”, the solution proposed here does not rely on IDMP identifiers. Nonetheless, it takes into account, however, relevant IDMP identifiers and attributes which are already usable in the IPS, namely the Pharmaceutical Product Identifiers (PhPIDs), the Medicinal Product Identifier (MPID), and the Medicinal Product Package Identifier (PCID).

Note: IDMP Medicinal Product (MPID) and Medicinal Product Package (PCID) identifiers depend on the market authorization. The “same” product might therefore have different IDs if different authorizations have been received in different countries, while the PhPID should be the same. For the purpose of the IPS, future standards and implementation guides should define global product identifiers that do not depend on the drug registration process (as the Virtual Medicinal Product in SNOMED CT) and relate to IDMP identifiers.

Thus, in the absence of a global identification system for medicinal products, the solution proposed here is based on the approach initially adopted by the European cross-border services (epSOS and currently by the eHDSI project), reused by the IHE Pharmacy templates and more recently adopted (for specific cases) by the HL7 Pharmacy Medication statement templates. The main idea is to integrate local drug identifiers (e.g. product codes) with all the relevant identifying and descriptive attributes that may help the receiver to understand the type of product the sender is referring to, e.g.: active ingredients, administrative dose forms, strength, route of administration and package description.

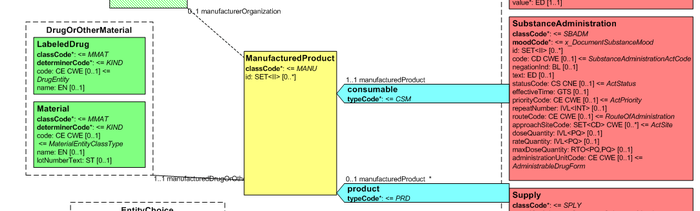

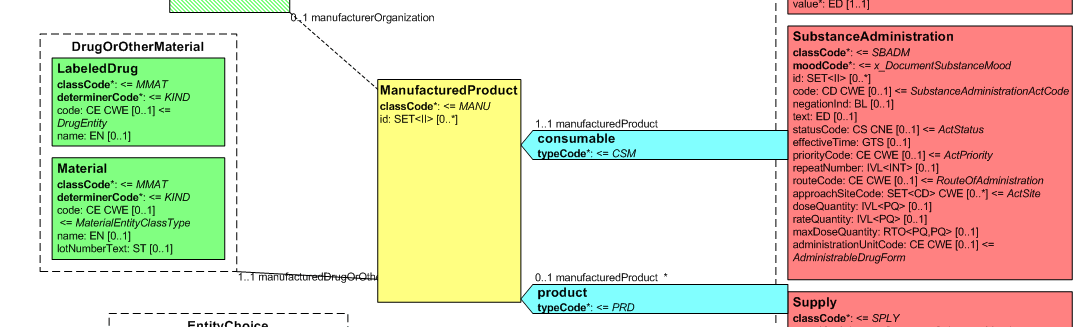

Medication data is usually represented in the CDA Templates using the manufacturedMaterial class, which includes a code and a name to describe any level of the product: packaged product, medicinal product, classes or clusters or products, and so on. This information is not however sufficient for covering the requirements of the IPS.

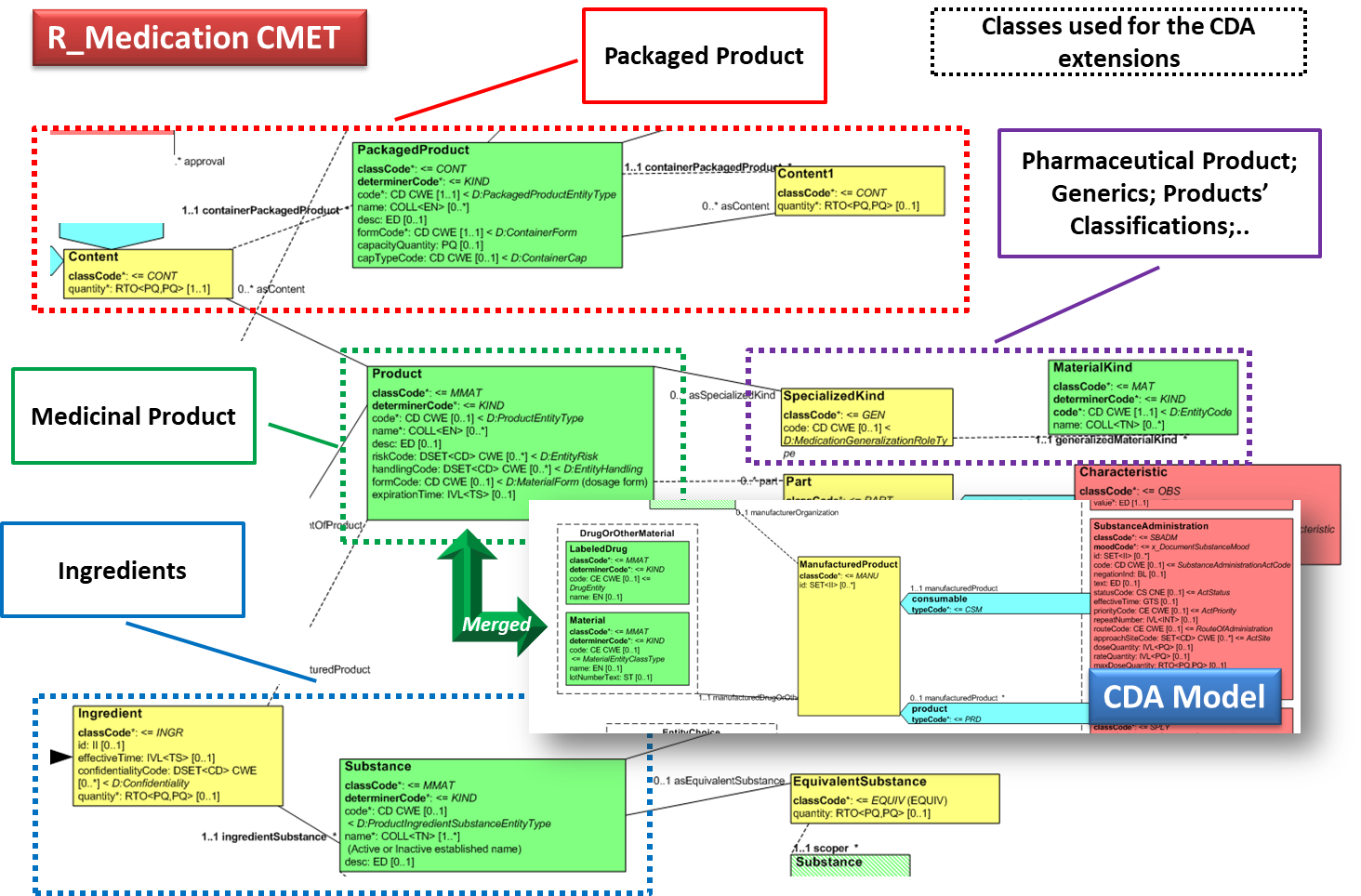

[Figure 11] Representation of medicines in CDA